The Free Market Center

I repeatedly hear from many very intelligent people that The Federal Reserve is raising or lowering interest rates. Statements like these are not true and cannot be true. As I have often said, interest rates are a dependent variable. You have to change something else to change an interest rate.

For those who listen to these comments and take them at face value, I would like to demonstrate how interest rates (or, more accurately, marginal interest rates) are calculated. This is pretty basic stuff, but please don’t dismiss it until you have completed this article. Understanding what The Federal Reserve can and cannot do plays an important role in understanding the various types of meddling done by the government and governmental agencies.To demonstrate how interest rates get changed, we must begin with an initial calculation

Interest results from the time preferences of parties exchanging present goods and future goods. Generally, a good has less value in the future than in the present. It’s up to individuals, based on their time preferences, to determine an acceptable amount of future good they will accept in exchange for a specific amount of current good.

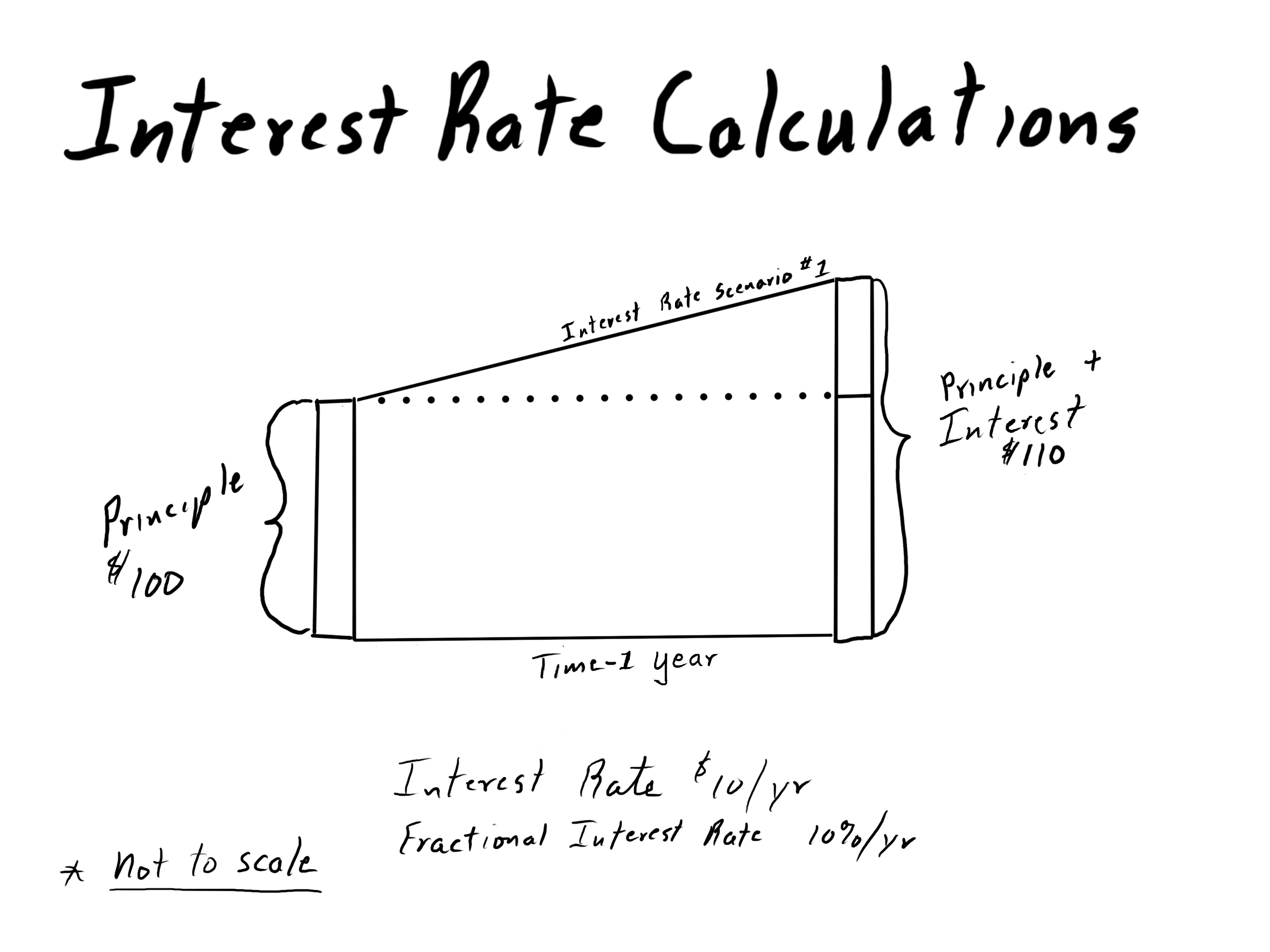

In this initial calculation, the actors agree to exchange $110 payable in one year for $100 in the present. The difference between the $100 of “principal” and the $110 in repayment amounts to interest. The rate of interest amounts to $10 per year. The marginal interest rate, commonly referred to simply as the “rate of interest,” amounts to 10% per year. In common usage, people refer to the marginal interest rate (or the interest rate”} so they can compare different amounts of principal and interest over different lengths of time.

The basic calculation is very simple. The difference between the amount borrowed and the amount repaid we call interest. The marginal rate of interest (which I will refer to as the “interest rate”) consists of the slope of the line between the amount borrowed and the amount repaid. The steeper the slope the higher the interest rate.

A diagram of a calculator

In the following scenarios, I will demonstrate what causes interest rates (i.e., marginal interest rates) to increase. Decreasing interest rates simply invert the calculation.

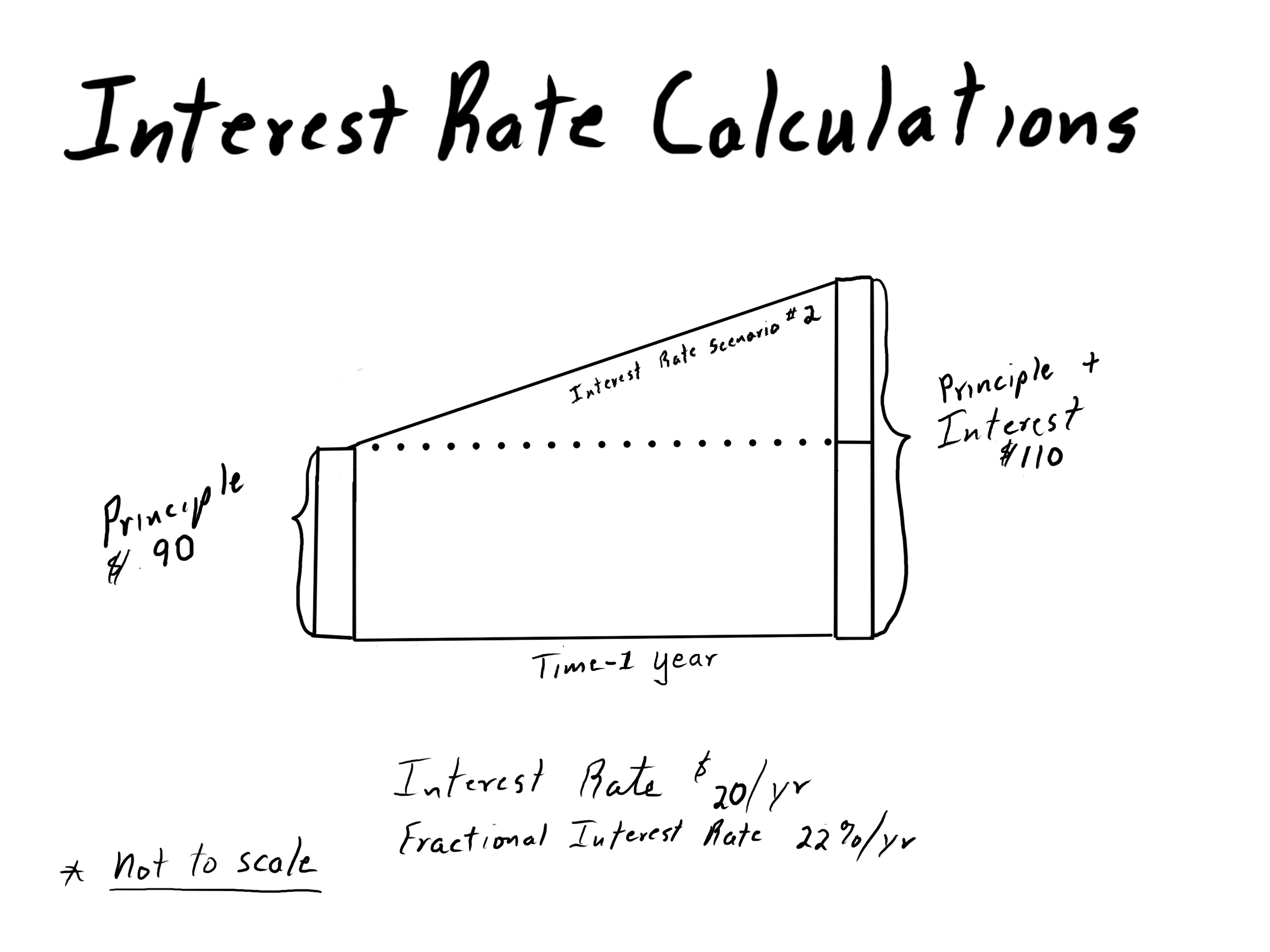

In the second scenario, the holder of the principal will only offer $90 for $110 paid after a year. As a result of this reduction in the amount of principal, the interest rate increases from 10% to 22%.

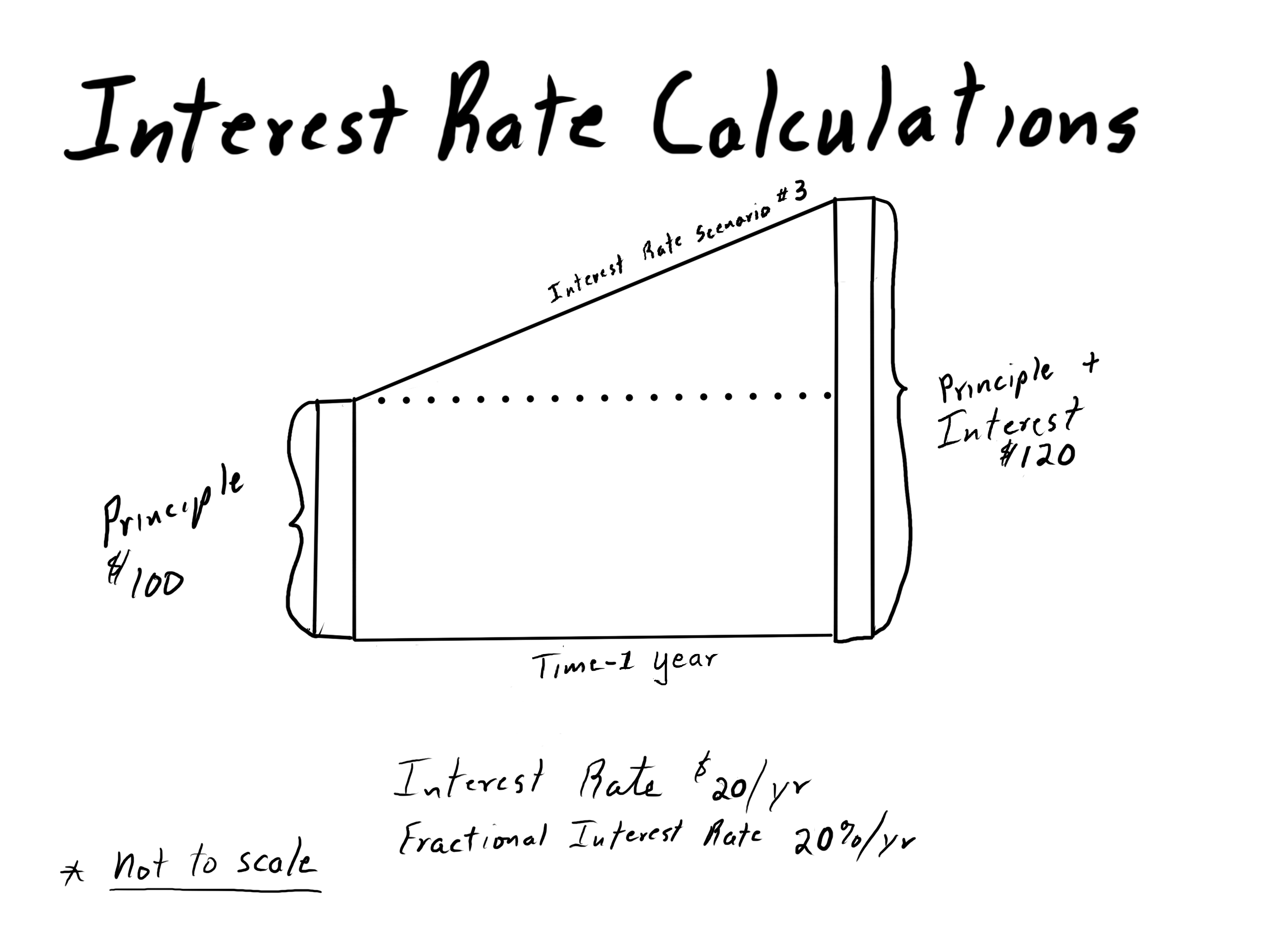

In this third scenario, the holder of the principal again offers $100, but in exchange, he will accept no less than $120, which the borrower willingly accepts.

In this case, the interest rate increases to 20% per annum.

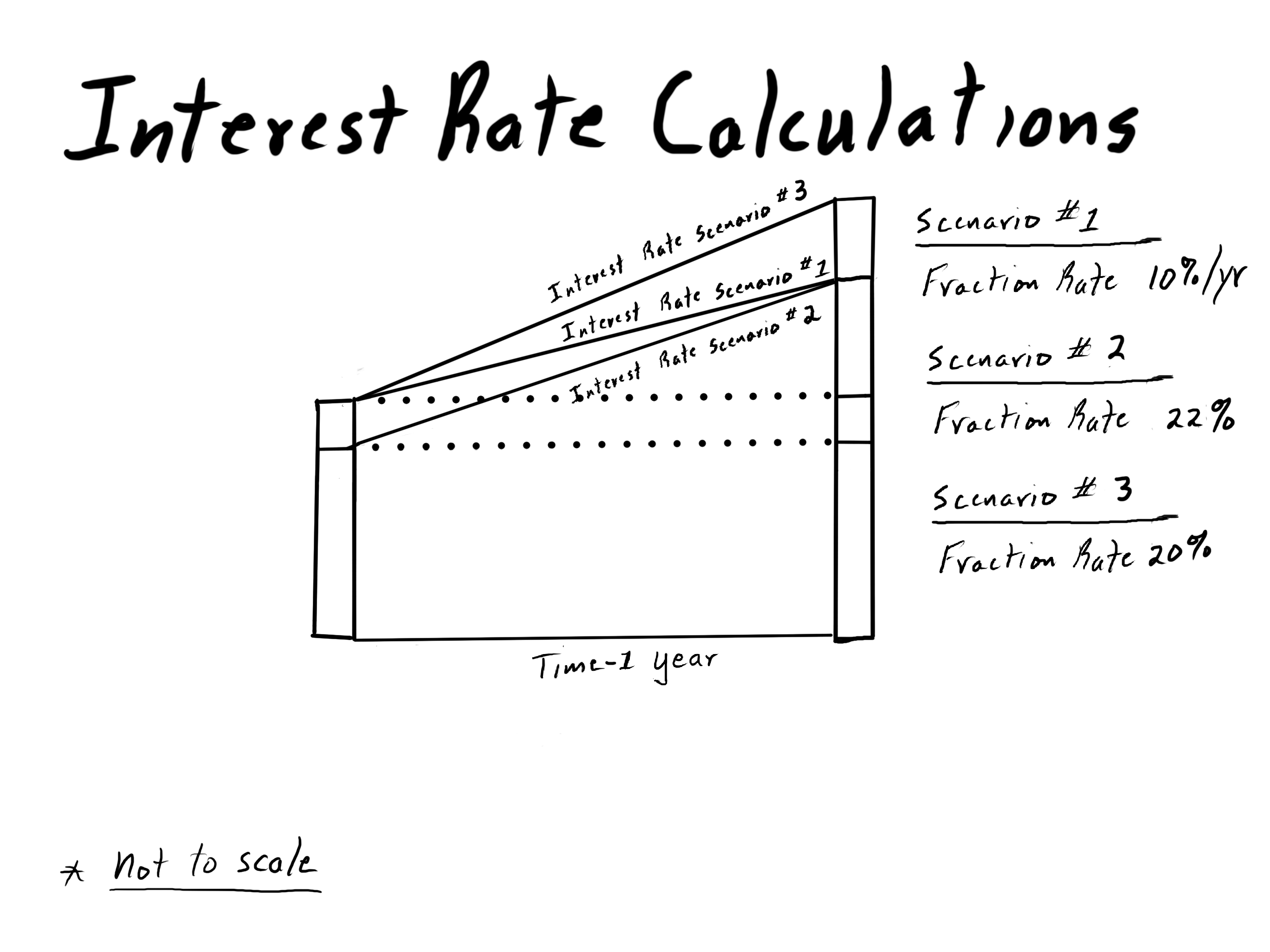

In this graphic, I have combined all three scenarios for visual effect. You can see that the interest rate will increase if either the lender reduces the principal amount or the borrower increases the repayment amount.

This graphic demonstrates clearly that interest rates cannot be changed unilaterally. To increase the interest rate, either the principal must be reduced or the amount of the repayment must be increased.

For the mathematician, this might seem like demonstrating a distinction without a difference. Mathematically, that might be true, but for the economist, this distinction does make a difference.

Loan transactions for which interest rates are calculated occur between separate individuals, not by a single person or institution. The situations and outside circumstances of lenders and borrowers might be entirely different. The supplier of the principal might only have a certain amount of money available. The “borrower” might be represented by a fixed amount of repayment, e.g., in the case of a bond; in this case, the interest rate is set by the owner of the principal, i.e., the buyer of the bond.

There are innumerable influences on such a transaction, but the fact remains that no individual party can control the rate of interest.

If you learn nothing else from this essay, remember it requires two parties to change an interest rate.

© 2010—2020 The Free Market Center & James B. Berger. All rights reserved.

To contact Jim Berger, e-mail: